Andy Blunden: Project-oriented theoretical approach [Activity Theory]

![Andy Blunden: Project-oriented theoretical approach [Activity Theory]](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1634137886474-b73ed1f67e46?crop=entropy&cs=tinysrgb&fit=max&fm=jpg&ixid=MnwxMTc3M3wwfDF8YWxsfDI1fHx8fHx8Mnx8MTYzNDE2MDEwNQ&ixlib=rb-1.2.1&q=80&w=960)

Andy Blunden’s Project-oriented theoretical approach is a major development of Activity Theory in the past decade.

According to Blunden, “Activity Theory has its roots in Classical German philosophy especially that of Hegel, in particular as appropriated by Marx (1845), as set out in Theses on Feuerbach. The proximate source of Activity Theory is the Cultural Psychology of Lev Vygotsky. On these foundations, A.N. Leontiev first set out a framework for Activity Theory, elaborated, for example, in The Development of Mind (2009) and Activity, Consciousness and Personality (1978). These foundations were further developed by a number of Soviet writers, by Yrjö Engeström with his Learning by Expanding (1987) followed by numerous journal articles and book chapters, and separately by a number of researchers in Europe.” (2014, p.23)

For Activity Theory, human actions and experiences are organized with “hierarchy”, “system”, “temporal chains”, “project”, “concept” and “network”. Schatzki’s hierarchical structure of social practice is very similar to Leontiev’s hierarchical structure of human activity. The jump from “action” to “activity” makes a simple but powerful thinking tool for theorizing “social”.

Activity: Aggregate of Actions

According to Blunden, “An activity or project is an aggregate of actions, so the conception of a project rests on the conception of action. In Activity Theory actions are both subjective and objective — behavior is not abstracted from consciousness. Consequently, an aggregate of actions is also equally objective and subjective. Implicit in the concept of ‘action’ is that actions are artifact-mediated; that is, all actions are effected by means of tools or symbols meaningful within the project and usually within the wider culture. Consequently, activities are also inclusive of the material conditions they both create and presuppose.” (2014, p.23)

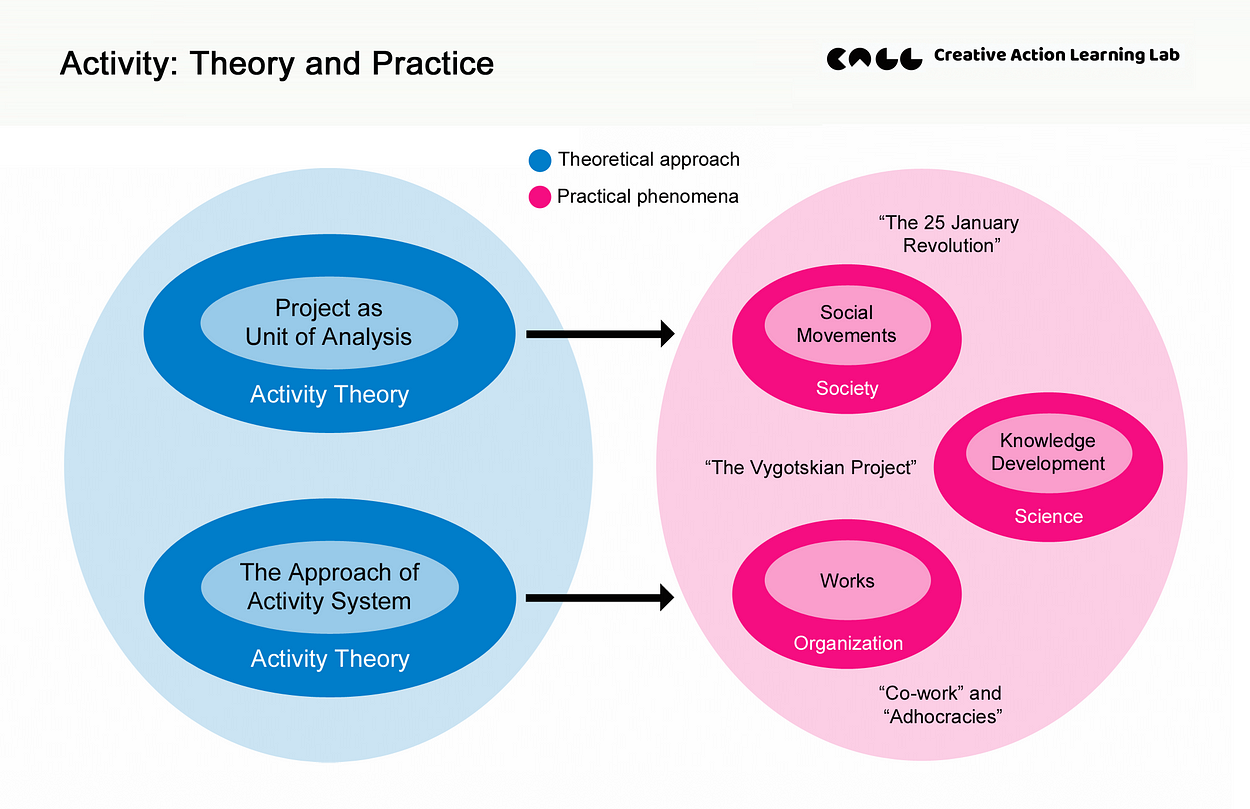

Activity Theorists don’t adopt temporality as a theoretical foundation for understanding the “aggregate of actions”. For example, Yrjö Engeström uses “system” and Andy Blunden uses “project” to aggregate actions and develops theoretical approaches. The diagram below presents these two approaches.

According to Andy Blunden, “In Activity Theory there is nothing in an activity other than human actions, and this is a thesis with which contemporary interactionist theories would be in agreement, eschewing recourse to biological determinism, religious or structural fatalism or any other force of human action as determinants of human life. But because there is nothing other than human actions to be found in an activity this does not mean that an activity is simply the additive sum of actions. In fact, the activity is generally a precondition for any of the component actions which instantiate it: when we act we do not generally create an activity, we join it. So Activity Theory recognizes that there are aggregates of actions which have a unity of their own for which, as the saying goes, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The question then is what is it that gives an activity its unity?” (2014, p.24)

In the above paragraph, Blunden sets the ontological foundation of “Activity” for Activity Theory. I think all Activity Theorists would agree with this statement. The question Blunden pointed out in the last sentence leads us to the epistemological level in which different Activity Theorists provide their own answers.

Andy Blunden’s Strategy and Motivation

Andy Blunden's strategy is expanding Activity Theory into an interdisciplinary theory of activity from its original version of psychological theory. Blunden’s goal is to develop a philosophical theory that can compete with Phenomenology and Existentialism at the Meta-theory level. He said, “What distinguishes Activity Theory from Phenomenology and Existentialism is that for Activity Theory, the project has its origin and existence in the societal world in which the person finds themself; for Phenomenology and Existentialism the psyche projects itself on to the world. For Activity Theory, commitment to a project and formulation of actions towards it, are mediated by the psyche, but a project is found and realized as something existing in the world, be that an entire civilization, a single personality, or anything in between. (See MacIntyre, 1981, p.146)” (2014, p.7). Thus, Blunden doesn’t start from an organizational work setting.

In order to develop the theoretical foundation of “Project as a unit of Activity”, Blunden adopts Hegel’s Logic and Vygotsky’s theory about Concepts as theoretical resources. The process is documented in three books: An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity (2010), Concepts: A Critical Approach (2012), and Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study (2014).

The solution of “Project as a unit of Activity” is summarized in a paragraph at the end of Introduction to Collaborative Projects. Blunden said, “How can we understand the relation between the motivation of individual actions on one hand, and on the other hand, the immanent objective of the project which forms the unifying principle of the project uniting all the disparate individual actions into a single activity? Hegel resolved this problem in his solution to the problem of the subsumption of any number of individual actions under a concept, but there is no criteria other than the concept itself determining this subsumption. The relation between an action and the project which gives to the action its rational meaning is the same as the relation between any individual discursive act and the concept which it instantiates, and the same as the relation between any individual thing and the category under which the thing is subsumed. The relation between the individual and the universal is mediated by the particular, that is by praxis, and it not to be conflated with the subjective-objective relation which is a quite distinct relation. The universal has no separate existence, but exists only in and through its particularization by individuals.”(2014, p.26)

What an amazing theoretical approach!

Project: Activity as Formation of Concept

It is hard to find some cases of empirical research which are based on the “Project-oriented Activity Theory” since it is a very young theoretical approach. According to Blunden, “…it has never been the intention of this project to create an alternative theory. The aim is to introduce into Activity Theory one new concept, the concept of ‘project’, which is to take the place of the unit of activity. All the past gains of Activity Theory and Cultural-Historical Psychology need to be retained. But the introduction of this new concept of the unit of activity will have not just an additive effect, but a transformative effect on theory as a whole. The notions of the norms and rules, instruments, community, etc., and the understanding of interaction between activities will be radically changed by the introduction of ‘project’ as a unit of analysis. But it is early days. This book marks only the very first effort. It is vital that everything we have learned about the internal structure and dynamics of activities (a.k.a. ‘systems of activity’ or ‘projects’) needs to be sublated into the concept of ‘project’ if it is to become a genuinely useful concept for the human sciences.” (2014, p.370)

After deliberately reviewing the unique theoretical concept of “Project-oriented Activity Theory”, I was attracted by its significance and promising prospect. So, what’s the value of the notion of “Project as a unit of activity” at the empirical research level?

Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study collects 25 case studies of “projects”. Blunden invites 25 authors to write one chapter for their own projects. According to Helena Worthen who is one of 25 authors, the book is a collection of stories. As Worthen remarks, “It’s probably better to look at the whole book and see what the people writing in it mean by ‘project.’ It draws together a range of reports that make a good argument for rethinking what they should be collectively called. Blunden calls them ‘research,’ and they certainly research. But they are also stories. All the chapters are narratives of something that happened. They involve many people and tell about something that happened over time. There are pauses, when the writers reflect on how the narrative is moving along, but above all the story keeps going…Over time, trial and error clarifies the project until it becomes something recognized, named and acknowledged…In most chapters, there is a point at which some part of the project becomes emblematic of the whole project.” (2014, p.357)

Worthen asks the same question about the practical value of “Project as a unit of activity”. She says, “In reading through this book, I kept asking myself how I would explain to someone who is not a social scientist how you would use either the project unit of analysis or the whole analytic framework of Activity Theory.” (2014, p.359)

Blunden argues that narrative explanation is going to play a central role in social science, especially the interdisciplinary Activity Theory which is considered a relatively young branch of science. (2014, p.369) Though I accept the narrative explanation as a way of producing scientific knowledge, I think it is also possible to develop some concrete theoretical models for “conceptual” analysis works.

For example, Blunden emphasizes the importance of the concept of Time in Activity Theory, “What the use of ‘project’ as a unit of analysis has done is to introduce into the unit of analysis of Activity Theory the element of time, which, though perhaps we never noticed, was previously absent.” (2014, p.369) This argument echoes my recent works, I recently reviewed the concept of “Chain” in Activity Theory and developed a new approach called Life-as-Activity for connecting Activity Theory and biographical studies.

In my opinion, the best sparkle of the notion of “Project as a unit of activity” is the idea of “Activity as Formation of Concept”. Let’s repeat Blunden’s own words, “…Hegel resolved this problem in his solution to the problem of the subsumption of any number of individual actions under a concept, but there is no criteria other than the concept itself determining this subsumption.”