Project-oriented Activity Theory (Summary)

The TOC and Introduction of my 2021 book Project-oriented Activity Theory

Contents

Introduction

Part 1 The Landscape of Activity Theory

Chapter 1 The Brief of Activity Theory and CHAT

Chapter 2 The Hierarchy of Human Activity

Chapter 3 The Engeström’s Triangle

Chapter 4 Typology of Activities

Part 2 Andy Blunden’s New Approach

Chapter 5 Project as "Objective of Activity"

Chapter 6 Project as a Unit of Activity

Chapter 7 Project as "Formation of Concept"

Chapter 8 A Brief of Andy Blunden's Approach

Chapter 9 Activity as Formation of Concept

Chapter 10 The Objectification of Concept

Chapter 11 The Landscape of Culture

Chapter 12 The Source of Activity

Chapter 13 A Theory of Radical Innovation

Part 3 Project Engagement

Chapter 14 Cultural Projection

Chapter 15 Projectivity

Chapter 16 Developmental Project

Chapter 17 Ecological Zone

Chapter 18 Zone of Project

Chapter 19 136 Ideas for Impact Projects

Part 4 Life as Activity

Chapter 20 The Historicality of Individuals

Chapter 21 Life as Temporal Activity Chains

Chapter 22 General Life Chains

Chapter 23 Mapping Specific Issues

Appendix 1 Knowing by Curating

Appendix 2 When Theory Meets Practice

Introduction

This book is a by-product of the Activity U project. I started learning Activity Theory, Ecological Psychology, and other theories around 2015. In August 2020, I initiated the Activity U project which aims to review the landscape of Activity Theory and CHAT (Cultural-historical activity theory) by reading and writing. I consider the project a knowledge curation project.

In October 2020, I wrote a post to review the first year of CALL (Creative Action Learning Lab) which is my personal studio. I claimed that Activity Theory is a learning object for Transdisciplinary Thinking which means the knowing between academic domains and non-academic domains. I pointed out four reasons for selecting Activity Theory for Transdisciplinary Thinking:

- It is an established theoretical tradition.

- It is an interdisciplinary philosophical framework for studying both individual and social aspects of human behavior.

- It has inspired many empirical studies in various domains.

- Its root is in a cultural background and psychological research tradition outside North America.

The last reason is unique. In a general sense, the mainstream of North American psychology is dominated by individual perspectives. In contrast, the psychological root of Activity Theory is the social perspective. Thus, I want to bring a new perspective to the next generation of knowledge workers and boundary creators in North America.

Contents

1. A Knowledge Curation Project

2. Andy Blunden’s version of Activity Theory

3. Project-oriented Activity Theory

4. How to read this book?

5. How do I explain Andy Blunden’s new approach?

6. How do I expand Andy Blunden’s new approach?

7. Life as Activity

8. A Theory of Radical Innovation

1. A Knowledge Curation Project

I have been working in the curation field for over ten years. I was the Chief Information Architect of BagTheWeb which was an early tool for content curation (We launched the site in 2010). This experience inspired me to make a long-term commitment to the Curation theme. After having 10 years of various curation-related practical work experiences and theory learning, I coined a term called Curativity and developed it as Curativity Theory.

From Sept 2018 to March 2019, I wrote a book titled Curativity: The Ecological Approach to Curatorial Practice. The book presents the Curativity Theory with a theoretical foundation Ecological Practice approach.

After March 2019, I continuously worked on revising Curativity and developing the Ecological Practice Approach as a new project. For the direction of Curativity Theory, I am looking for practical applications, for example:

- Knowledge Curation

- Action Curation

- Life Curation

- Platform Curation

I have written a chapter discussing knowledge curation in the book Curativity. For academic knowledge curation, I mentioned Dean Keith Simonton’s Chance-configuration Theory, Victor Kaptelinin and Bonnie A. Nardi’s scientific curation case study “curation at Ajaxe,” and qualitative research. For practical knowledge curation, I focus on Cognitive Container since Container is a core concept of Curativity Theory.

Books and courses are typical cognitive containers, however, there are more types of cognitive containers. I highlighted the following five types of Cognitive Containers:

- Knowledge Card

- Knowledge Framework

- Knowledge Diagram and Chart

- Knowledge Workshop

- Knowledge Sprint

It is not an accurate classification, but a rough recommendation. Also, I suggested that we not only adopt existing types of cognitive containers but also create new types of cognitive containers. Actually, this is the essential point of the Curation Theory. We are shaped by containers and we can make containers too.

The Activity U project started from the HERO U framework and diagram. I consider the HERO U framework as “an ecological approach of knowing” because it refers to the structure of “organism (personal conditions of knowing) — action (knowing) — environment(objective of knowing)”. The U diagram presents six types of Objective of Knowing: mTheory (Meta-theory), sTheory (Specific Theory), aModel (Abstract Model), cModel (Concrete Model), dPractice (Domain Practice), and gPractice (General Practice). The second dimension (red balls) presents a set of Personal Conditions of Knowing: Concept, Diagram, Problem, Method, Resource, Tools, and Domain.

The foundation of Activity Theory and CHAT, in general, is Lev Vygotsky’s idea of “mediated action.” Vygotsky claimed that human action and psychological functions are mediated by tools which refer to technical tools that work on objects and psychological tools that mediate the mind and environment. The idea of “mediated action” is usually represented by a triangle that contains three elements: subject, mediating artifact/tool, and object. If we use this model to explain the first stage of the Activity U project, we get the following diagram.

Though the name Activity U refers to Activity Theory and CHAT (Cultural-historical Activity Theory), I also consider other related theoretical approaches for my learning objects. For example, Vygotsky’s Cultural-historical psychology, Marxism, and practice theories.

According to Nikolai Veresov (2020), “Both CHAT and cultural-historical theory emphasise the importance of cultural mediation in the process of formation of identity as a sociocultural phenomenon. However, they provide different perspectives in relation to what is the basic unit of analysis. For CHAT this unit is a mediated action; cultural-historical theory emphasises dialectical and dynamic aspects by introducing the mediating activities of an individual within changing social environments. In other words, cultural-historical theory is not focused on mediated actions, but on a human being who uses or creates cultural tools in order to reorganise the social situation and overcome existing challenges.”

We should pay attention to the difference between “mediated action” and “mediating activities.” For Vygotsky, “Man himself determines his behavior with the help of artificially created stimuli-devices…human behavior was determined not only by the stimuli present, but by a new or changed psychological situation created by the man himself. (Vygotsky 1977, pp. 49–54)”. Thus, the essential part of the Activity U project is the action of creating and using the HERO U framework and diagram which can be considered as “cultural tools”.

However, the Activity U project went beyond the HERO U framework during the writing process. I started to expand it by adding more “social aspects.” The “U” of “Activity U” became “You” which refers to the potential audiences of my articles and potential learners of Activity Theory and Transdisciplinary Thinking.

Also, I was motivated by Bonnie A. Nardi’s story. Bonnie A. Nardi is an activity theorist, HCI researcher, and anthropologist. She is well known for her work on activity theory, interaction design, games, social media, and society and technology. The third article of Activity U is about her story: Activity U (III): Bonnie Nardi’s Choices and Boundary Knowledge Work.

What I learned from Nardi is not only about the knowledge of applying Activity Theory to the HCI field, but also the attitude of Appropriating Theory. I am not saying everyone needs to learn theory, I just personally believe in the value of theory. In other words, Nardi influences me on the level of personal epistemology which is about an individual’s belief in knowledge and knowing.

To be honest, I didn’t know Andy Blunden before August 2020 when I started the Activity U project. During the writing process, I found a book review on Clay Spinuzzi’s blog. Since then, I started to read Andy Blunden’s books and papers and created a branch of the Activity U project for introducing Blunden’s Project-oriented theoretical approach.

This book is a collection of my articles for introducing Blunden’s Project-oriented theoretical approach. It’s a pleasure to work on the Activity U project and this book. On Aug 20, 2020, I shared HCI-Activity Theorist Bonnie Nardi’s story and suggested the concept of Appropriating Theory as a way of knowing. Now I have a deep understanding of the concept of Appropriating Theory.

2. Andy Blunden’s version of Activity Theory

Activity Theory or the “Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT)” is an interdisciplinary philosophical framework for studying both individual and social aspects of human behavior. Activity Theory is an established theoretical tradition with several theoretical approaches developed by different theorists. Originally, it was inspired by Russian/Soviet psychology of the 1920s and 1930s.

A major development of Activity Theory during the past decade is Andy Blunden’s account “An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity.” Andy Blunden is an independent scholar in Melbourne, Australia. He works with the Independent Social Research Network and the Melbourne School of Continental Philosophy and has run a Hegel Summer School since 1998.

Blunden’s vision of the interdisciplinary theory of Activity is inspired by Vasily Davydov’s argument:

“I always argue that the problem of activity and the concept of activity are interdisciplinary by nature. There should be specified philosophical, sociological, culturological, psychological and physiological aspects here. That is why the issue of activity is not necessarily connected with psychology as a profession. It is connected at present because in the course of our history, activity turned out to be the thing on which our prominent psychologists focused their attention as early as in the Soviet Union days. Things just turned out this way. (Davydov, 1999: 50.)”

In order to develop the notion of “Project as a unit of Activity” as a theoretical foundation of the new interdisciplinary theory of Activity, Blunden adopts Hegel’s logic and Vygotsky’s theory about “Unit of Analysis” and “Concept” as theoretical resources. The process is documented in four books: An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity (2010), Concepts: A Critical Approach (2012), Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study (2014), and Hegel for Social Movements (2019).

An essential challenge of theorizing “activity” in an interdisciplinary way is the source of activity. In other words, how is it possible to claim that there is an “activity” which contains various actions?

According to Andy Blunden, “In Activity Theory there is nothing in an activity other than human actions, and this is a thesis with which contemporary interactionist theories would be in agreement, eschewing recourse to biological determinism, religious or structural fatalism or any other force of human action as determinants of human life. But because there is nothing other than human actions to be found in an activity this does not mean that an activity is simply the additive sum of actions. In fact, the activity is generally a precondition for any of the component actions which instantiate it: when we act we do not generally create an activity, we join it. So Activity Theory recognizes that there are aggregates of actions which have a unity of their own for which, as the saying goes, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The question then is what is it that gives an activity its unity?” (2014, p.24)

In his 2010 book An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity, Blunden traces the roots of Activity Theory from Goethe, Hegel, and Marx in order to present an immanent critique of Activity Theory and its contemporary version CHAT. The core of Blunden's argument is a theoretical methodological issue: Unit of Analysis. For Blunden, the concept of “Unit of Analysis” should be understood as Goethe’s Urphanomen which is also known as the ‘cell’. Blunden believes that the unit of analysis should be followed by an explanatory principle of “the part contains the whole”. In other words, if we want to understand a complex phenomenon, we should start with the most primitive form of the phenomenon. For activity theorists, if they agree that their theoretical roots are ideas from Goethe, Hegel, Marx, and Vygotsky, then they have to respect this methodological criticism because the Urphanomen principle has been adopted by all of these predecessors.

Blunden adopts the Urphanomen principle and suggests a new unit of activity for developing an interdisciplinary theory of Activity. He says, “A project is something projected by the subject, rather than an object to which the subject is drawn; the subject may be an individual or many people who are united precisely in that they are pursuing the same project. A project is an on-going collection of actions and is both the aim of the actions and the process of attaining that object. A project is a concept, but every individual has a different concept of the project, these constituting the various shades of meaning and connotations to be found in representations of the project. People may be fully committed to the project, or they may pursue the project for external rewards provided for their participation; people may ‘own’ a project, or be only barely aware of its existence.” (2010, p.9)

The solution of “Project as a unit of Activity” is summarized in a paragraph at the end of Introduction to Collaborative Projects. Blunden said, “How can we understand the relation between the motivation of individual actions on one hand, and on the other hand, the immanent objective of the project which forms the unifying principle of the project uniting all the disparate individual actions into a single activity? Hegel resolved this problem in his solution to the problem of the subsumption of any number of individual actions under a concept, but there is no criteria other than the concept itself determining this subsumption. The relation between an action and the project which gives to the action its rational meaning is the same as the relation between any individual discursive act and the concept which it instantiates, and the same as the relation between any individual thing and the category under which the thing is subsumed. The relation between the individual and the universal is mediated by the particular, that is by praxis, and it not to be conflated with the subjective-objective relation which is a quite distinct relation. The universal has no separate existence, but exists only in and through its particularization by individuals.” (2014, p.26)

Blunden also gives an archetypal unit of project in his 2010 book An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity.

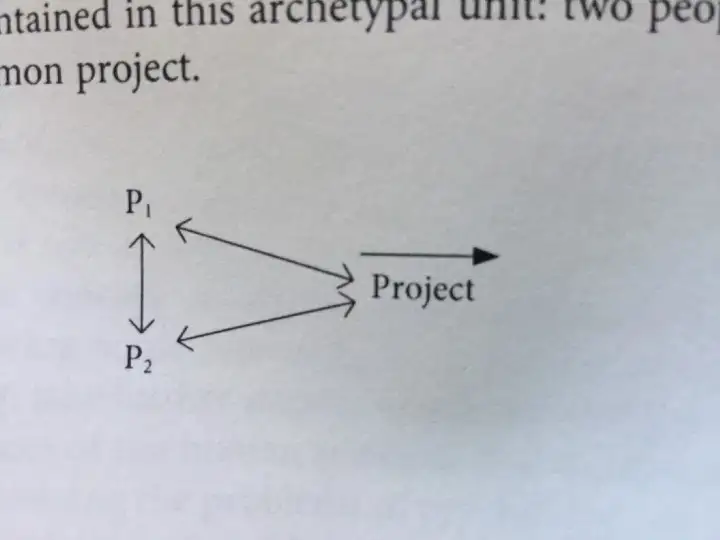

He says, “The rich context of the notion of collaboration also brings to light more complex relationships. The notions of hierarchy, command, division of labor, cooperation, exchange, service, attribution, exploitation, dependence, solidarity, and more can all be studied in the context of just two individuals working together in a common project. And yet almost all the mysteries of social science as well as a good part of psychology are contained in this archetypal unit: two people working together in a common project.” (2010, p.315)

Blunden’s 2012 book Concepts: A Critical Approach continues the journey. Blunden reviews the theoretical development of Concepts in an interdisciplinary approach which curates theories about Concepts from various disciplines such as cognitive psychology, analytic philosophy, linguistics, and the history of science. He adopts Hegel’s theory of concept and Lev Vygotsky’s cultural-historical psychology as theoretical resources and proposes a new approach to Concepts. He argues that concepts are equally subjective and objective: units both of consciousness and of the cultural formation of which one’s consciousness is part. In other words, the formation of concepts is an activity.

“Project as a unit of activity” and “formation of concept is activity” are combined in Blunden’s 2014 book Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study which is a collection of twelve research reports with a common theme. As the editor of the book, Blunden invites his friends to write a report about a concrete collaborative project and write a review on their story. The book also contains an introduction and a conclusion which are written by Blunden. In addition, Blunden also writes a case study about “Collaborative Learning Space” which was initiated by him in 1999.

What Blunden suggested is that 1) We can use “Project” as a new unit of analysis for Activity Theory, 2) Project should be understood as a formulation of the concept, and 3) The archetypal unit of “Project” is two people working together in a common project.

In the first ten years of the 21st century, Blunden laid a new foundation for Activity Theory in an age of information overload and platform capitalism. According to Blunden, “CHAT is already an emancipatory science. It is committed to the ethos of self-emancipation. It does not seek to control people, test them or predict their behavior, but rather to join people in striving for their own goals…CHAT aims at the self-determination of human beings. We can not do this with concepts which fail to capture the essential nature of human activity as being tied up with the projection of our ideals, however mistaken they may be from time to time. But self-determination is never that of being an island. Self-determination, or sovereignty, is about participation in the self-determination of oneself and others, together as equals, through collaborative projects.” (2010, p.317-318)

In 1975, Charles A. Lave and James G. March published a book titled An Introduction To Models in The Social Sciences. They suggested an interpretation of the evaluation of models, “What we present here are some rather simple points of view about truth, beauty, and justice that we, and others, have found helpful in heightening the pleasures and usefulness of model building in social science.”

I think this simple idea is also helpful for the evaluation of theories. I am not sure if we can claim that Blunden’s approach has a strong aspect of truth. However, I think his approach is simple, which is the principle of beauty. Finally, what Blunden wants to build is an interdisciplinary science about self-emancipation which refers to justice.

It takes time to raise a new theoretical approach. As Blunden pointed out, “…But it is early days. This book marks only the very first effort.”(2014, P.370) Also, it takes a village to raise a child. The development of a theoretical approach is a collaborative project. We need more people to echo Blunden’s vision.

3. Project-oriented Activity Theory

Andy Blunden doesn’t use “Project-oriented Activity Theory” as an official name for his approach. Originally, I used this term to refer to Blunden’s approach. Now I realize the name becomes an issue because my articles present my interpretation of Blunden’s approach.

It is clear that I add some new ideas to expand Blunden’s original approach. Thus, we can use the name to refer to three things: 1) Blunden’s original approach, 2) My interpretation of Blunden’s approach, 3) Blunden’s original approach, my interpretation, and other interpretations and applications.

I suggest that we adopt the name to describe the whole account which is initiated by Blunden.

The following list can help readers distinguish Blunden’s original approach and my interpretation:

- I designed a series of diagrams for Blunden’s approach.

- I added “Projectivity” and “Zone of Project” as two theoretical concepts to the original approach. Some theoretical resources behind “Projectivity” and “Zone of Project” are adopted from Ecological Psychologists.

- I made a distinction between “Idea” and “Concept” in order to keep the term “Project” for both normal works and social movements.

- Blunden’s original approach doesn’t adopt the Activity System model. I claimed that it is possible to keep Blunden’s approach and the Activity System model within a theoretical framework by distinguishing between Idea and Concept. In this manner, we can grow Activity Theory without discarding the Activity System model since it is an established branch of Activity Theory.

- Based on the concept of “Projectivity”, I develop a model called “Cultural Projection Analysis”.

- I find a connection between my own idea “Themes of Practice” and Blunden’s “Formation of Concept.” I consider “Theme” as a special type of “Concept.” Based on “Formation of Concept,” I adopt “Themes of Practice” for discussing the internal structure and dynamics of Projects. In particular, I identify five “Themes of Practice” of Projects: “Idea”, “Resource”, “Program”, “Performance” and “Solution”.

- I found a connection between my own idea “Ecological Zone” and Vygotsky’s “Zone of Proximal Development.” I also noticed that Blunden gives an archetypal unit of project in his 2010 book An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity: two people working together in a common project. By curating these ideas together, I developed a new concept of “Zone of Project” which can be considered as an expansive work of Blunden’s archetypal unit of Project.

- In addition, I develop “Developmental Project” as a new intermediate concept for applying Project-oriented Activity Theory to study knowledge works and the development of knowledge workers. I also developed the Developmental Project Model for practical studies.

The most important difference between Blunden’s original approach and my interpretation is that his vision is developing a general interdisciplinary theory of Activity as a meta-theory. However, my vision is to adopt his meta-theory and develop some frameworks and models for practical studies. Also, my focus is knowledge work and knowledge workers.

In the article CALL: The House of Boundary Innovation, I mention that I choose ‘transdisciplinary thinking’ to refer to the knowing between academic domains and non-academic domains. According to the editors of The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity (2010), there are two words about inter- or transdisciplinary knowledge production. The ‘interdisciplinarity’ refers to current efforts of knowledge production that cross or bridge disciplinary boundaries and the ‘transdisciplinarity’ refers to the growing effort to make knowledge products more pertinent to non-academic actors. However, in the US, ‘interdisciplinarity’ covers both the integration of knowledge across disciplines, narrow and wide and the intercourse between (inter)disciplines and society. The latter often goes by the name of transdisciplinarity, particularly in Europe (p.xxx).

Now we can consider two ways of growth of a theory of Activity. While Andy Blunden works on expanding Activity Theory from a psychological theory to an interdisciplinary theory, I work on expanding his meta-theory from academic domains to non-academic domains with the mindset of ‘transdisciplinary thinking’.

I encourage readers to read Blunden’s original books and develop their own frameworks and models. Together, we can build a community of Project-oriented Activity Theory.

4. How to read this book?

This book was not planned. It is a collection of several articles about Project-oriented Activity Theory. Though these articles are my learning notes, they are also considered as my proposal since I add many new ideas to expand Blunden’s original approach. I’d like to give readers a guide to reading these articles.

I designed the picture below to visualize my own thoughts behind the work. The picture has seven red balls: Domain, Resource, Tools, Problem, Method, Concept, and Diagram. These elements are from the HERO U framework (the article, the diagram). The seven red balls refer to Personal Conditions of Knowing. The first group is Domain, Resource, and Tools, they define the outside setting of the knowing activity. The second group is Method and Problem, which define the source of competence and solution. The third group is Diagram and Concept, which define the representation format of the outcome of knowing. These three groups form a process of knowing.

The above diagram represents the whole picture of my interpretation of Blunden’s approach. Readers can use this diagram as a map for reading my articles. The most important piece is the five steps.

- The first article provides some background for the work and focuses on one case study which is conducted by Andy Blunden.

- The second article uses a 3–3–3–1 schema to summarize Blunden’s approach. It also introduces a series of diagrams.

- The third article introduces the concept of Projectivity with a series of diagrams.

- The fourth article introduces the concept of "Zone of Project" through a two-step process of conceptual curation.

- The fifth article introduces a book and its website as a heuristic tool for developing ideas and concepts.

Readers can also pay attention to my methods: Immanent Development, Conceptual Curation, and Diagramming as Theorizing.

- Immanent Development: I adopt ideas from Blunden’s books and continuously develop these ideas. In particular, I use the “germ-cell” idea to guide the development of diagrams.

- Conceptual Curation: By curating ideas from the Cultural-historical theory of psychology and ecological psychology, I develop new concepts in order to expand Blunden’s original approach.

- Diagramming as Theorizing: I design a series of diagrams that help me better understand Blunden’s ideas. It could be useful for other learners who want to adopt Blunden’s approach.

If you are not familiar with Activity Theory and CHAT, you can read Part 1. I briefly introduce the landscape of Activity Theory and highlight several important concepts such as the hierarchy of human activity and the Activity System model.

5. How do I explain Andy Blunden’s new approach?

Part 2 introduces Andy Blunden’s new approach to Activity Theory. You can pay attention to four things: 1) diagrams, 2) examples, 3) the source of Activity, and 4) the evaluation of the new approach.

First, I designed a series of diagrams with a germ-cell diagram. One of three significant notions of Blunden’s approach is “germ-cell” which refers to the Goethe-Hegel-Marx-Vygotsky approach of “Unit of Analysis.” According to Blunden, “…in order to understand a complex process as an integral whole or gestalt, we have to identify and understand just its simplest immediately given part — a radical departure from the ‘Newtonian’ approach to science based on discovering intangible forces and hidden laws” (2020)

I applied the idea of “germ-cell” to diagramming. A germ-cell diagram is a special type of meta-diagram that can easily generate a diagram system with the same intrinsic spatial logic. A typical structure of a diagram system is a multiple-level analysis system. The first challenge of adopting a germ-cell diagram is to design a spatial logic that can apply to different levels of a multiple-level diagram system. In other words, we only need one spatial logic for the whole system since the one spatial logic is a whole.

The above diagram is a “germ-cell” diagram for Project-oriented Activity Theory. It is better to think about this diagram as a room with two windows and one door.

A room is a container that separates inside space and outside space. There are some actions people can do within a room. I pay attention to one special type of action: connecting to the outside space from the inside space. Let’s call it “Process.” The two windows are interfaces that refer to two “Tendencies,” Window1 refers to “Tendency 1” while Window 2 refers to “Tendency 2.” Each window has its own view of the outside space. Finally, there is a door that allows people to actually go out of the room. The door refers to “Orientation” which represents a direction of a real action of going out of the inside space. Once you get into the outside space, you can consider the new space as a new room and repeat the diagram.

This is a special type of spatial logic. The terms such as “Process”, “Tendency” and “Orientation” are placeholders of texts for describing the spatial logic. From the perspective of my diagram theory, the pure meta-diagram doesn’t need text. For instance, the Yin-yang symbol or Taijitu is a meta-diagram, can you find one text from it? However, we can add some texts as placeholders to a pure meta-diagram in order to better describe it.

Second, I used some examples to explain Andy Blunden’s ideas. The primary example is Blunden’s own case study: “Collaborative Learning Space.” In order to describe three movements of Concept (Universal, Individual, and Particular) and three aspects of Objectification of Concept, I used TEDx as an example.

Third, I identified three statements of “the Source of Activity.” For the development of Activity Theory, we know there are some existing statements about this issue. Based on Karl Marx and Lev Vygotsky’s ideas, A. N. Leontiev first set out a framework for Activity Theory and coined the statement of “Object-orientedness” which is a famous basic principle in the mainstream of Activity Theory literature.

We have to notice that what Blunden wants to develop is not a psychological theory, but an interdisciplinary social theory including individual psychological development as a part. Though the “Object-orientedness” principle is great for an activity-theoretical approach to psychological development, there is room for developing a new statement of “the Source of Activity” in order to establish an activity-theoretical approach to social theory.

Leontiev’s approach is further developed by Yrjö Engeström and others. Engeström upgraded the activity theory from the individual activity level to the collective activity level with a conceptual model of “activity system” in order to apply activity theory to educational settings, organizational development, and other fields (Engeström,1987). Engeström embraces the “Object-orientedness” principle and keeps the “Object” as a key concept of his “Activity System” model (the Engeström’s Triangle). Furthermore, he adopts the concept of “contradiction” for explaining the development of Activity Systems. In other words, the “Development by Contradictions” principle is Engeström’s statement to “the Source of Activity”.

Now I want to claim that Blunden establishes a new approach to Activity Theory by developing the concept of “Project” as a unit of Activity. The new approach is supported by the notion of “Activity as Formation of Concept” which is a brand new statement to “The Source of Activity.” We can call this statement the “Formation of Concept” principle.

In order to connect the statement “Object-orientedness” and the statement “Formation of Concept,” I made a distinction between Idea and Concept from the perspective of Project-oriented Activity Theory. The diagram below represents the notion visually.

According to Blunden, “The project arises in response to some contradiction or problem within a social situation. However, the object cannot simply be conceived of as ‘to solve problem X.’ The problem stimulates efforts to find a solution but it is not in itself sufficient to form a concept (Vygotsky, 1934/1987, p.126). Quite different, even mutually hostile projects may be directed at one and the same situation and solve one and the same problem. The formation of a project with a concept of the problem is an original and creative social act. ”(2014, p.25)

I have emphasized that we have to think of the “project” as the “formation of concept,” not a regular project such as work. The above diagram represents a path in which the idea defines an object and the object defines the work or regular activity. This path is covered by the statement of “Object-orientedness” which is initiated by Leontiev’s approach and supported by Engeström’s Activity System model. On the other hand, the “Idea” is a pre-concept process that can lead to the “Concept” and the “Project.” This path is the focus of Blunden’s approach.

It is clear that the statement of “Object-orientedness” is a sub-statement of the statement of “Formation of Concept” because the “Idea” process which leads to the object-defined regular works or activities is the pre-Concept process.

Fourth, at the end of Part 2, I offer an evaluation of the new approach from two sides: theoretical contributions and practical heuristic functions. I also reflect on my own experience and recommend some heuristic tools for readers.

6. How do I expand Andy Blunden’s new approach?

Part 3 moves to connect meta-theory and concrete frameworks in order to build a path for applying Project-oriented Activity Theory. Blunden doesn’t give a complete description of the internal structure and dynamics of Projects. He just reviews Yrjö Engeström’s Activity System model and comments on elements of the model. Part 3 offers a solution for understanding the internal structure and dynamics of Projects.

I introduce a new concept called “Projectivity” and use it as a foundation for building an intermediate framework called Cultural Projection Analysis. By adopting Blunden’s “Project as a Unit of Activity” and Cultural Projection Analysis, I develop two concrete frameworks called Developmental Project and Zone of Project.

The concept of Projectivity is inspired by Ecological Psychologist James J. Gibson’s Affordance theory. The concept of Zone of Project is inspired by Lev Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development and Ecological Psychologist Roger Barker’s Behavior Settings theory. Thus, we can consider Part 3 to be a dialogue between Activity Theory and Ecological Psychology.

The Ecological Zone framework is inspired by Ecological Psychology. In order to adopt the Ecological Zone framework to expand Andy Blunden’s new approach, I return to Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. One theoretical statement of the Ecological Zone framework is Themes of Practice. It is possible to consider “Development” as a Theme of Practice in a particular Ecological Zone. In order words, we can consider the “Zone of Proximal Development” as a special type of Ecological Zone. However, the missing piece is the part of the “Actual — Potential” of individual development. So, it is possible to adopt the idea of “Actual — Potential” of individual development from ZPD to expand the Ecological Zone framework.

The above diagram is a generalization of ZPD. While the “Teacher—Student” is replaced by “Self — Other,” the “Actual — Develop — Potential” remains. If we put this diagram and the Ecological Zone diagram together, we can consider this one as a reasonable extension of Ecological Zone because the development is driven by dramatic experience, according to Vygotsky.

The Ecological Zone framework is also inspired by Michael Cole’s level of analysis: Joint artifact-mediated activity. The Shared Activity of the Ecological Zone framework can be considered a Joint Activity. Though the diagram of Ecological Zone doesn’t highlight artifacts in a notable way, the Settings of Ecological Zone refers to artifacts, environment, and social context of shared activity, it echoes Michael Cole’s focus on artifacts, ecological and cultural contexts.

Thus, I believe it is possible to adopt the Ecological Zone framework to discuss the internal structure and dynamic of Projects.

7. Life as Activity

Part 4 introduces the Life-as-Activity approach as an intermediated framework for biographical studies and adult development. The approach adopts four activity-theoretical ideas as its foundation:

- Activity System model (Yrjö Engeström, 1987)

- Temporal Activity Chains (Paul Richard Kelly, 2018)

- Project orientation analysis (Andy Blunden, 2014)

- Zone of Proximal Development (Lev Vygotsky, 1933)

I also adopt several concepts from other theoretical resources about motivation, mental complexity, creative work, cultural life, organizational development, and self-knowledge. For example:

- Self-Determination Theory (Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, 1971, 2017)

- The constructive—developmental approach (Robert Kegan, 1982, 2009)

- The evolving systems approach to the study of creative work (Howard E. Gruber, 1974,1989)

- Culture Themes (Morris Opler,1945)

- Near Histories (James March, 1991)

- Possible Selves (Hazel Rose Markus, 1986)

Thus, the Life as Activity approach is not a pure application of Activity Theory, but an open toolkit that has two groups of theoretical concepts. The first group comes from Activity Theorists and sets the foundation for the approach. Without this foundation, we can’t call this approach an activity-theoretical approach. The second group comes from non-activity theorists and provides more tools for explaining individual life. Since there are many theories for the development of individual life, the second group is an open room for appropriating theories.

One important aspect of the Life-as-Activity approach is the concept of Reproduction of Activity. According to Andy Blunden (2014), “What distinguishes Activity Theory from Phenomenology and Existentialism is that for Activity Theory, the project has its origin and existence in the societal world in which the person finds themself; for Phenomenology and Existentialism the psyche projects itself on to the world. For Activity Theory, commitment to a project and formulation of actions towards it, are mediated by the psyche, but a project is found and realized as something existing in the world, be that an entire civilization, a single personality, or anything in between. (see MacIntyre, 1981, p.146)…a project is a concept of both psychology and sociology.” The Life-as-Activity approach adopts the project orientation analysis as the basis. Thus, it provides a systematic framework for all types of knowledge workers to reflect career development and domain development.

Outside Activity Theory, a major theoretical resource I adopted for the Life-as-Activity approach is the evolving systems approach to the study of creative work (Howard E. Gruber, 1974,1989). I really like this approach. However, the approach is used for researching major creators such as Charles Darwin, Jean Piaget, and Williams James. I want to apply this approach to contemporary knowledge workers.

Gruber’s core theoretical concept is “Network of Enterprise”. He uses the term “enterprise” to stand for a group of related projects and activities broadly enough defined so that (1) the enterprise may continue when the creative person finds one path blocked but another open toward the same goal and (2) when success is achieved the enterprise does not come to an end but generates new tasks and projects that continue it.” (1989, p.11)

I use both “projects” and “enterprise” for the Life-as-Activity approach. The “projects” also refers to Gruber’s “projects” which are part of “enterprise.” Activity Theory doesn’t provide a higher level concept than “activity” for organizing a group of activities. The notion of “Activity Network” is not for understanding personal life. Thus, I think Gruber’s “enterprise” is good enough for the Life-as-Activity approach.

8. A Theory of Radical Innovation

In my opinion, Project-oriented Activity Theory can be adopted as a theory of radical innovation since the approach covers the whole developmental process of a brand-new concept.

Organizational scholars use “Radical innovation — Incremental innovation” to discuss organizational innovation, “While incremental innovations are typically extensions to current product offerings or logical and relatively minor extensions to existing processes, radical product innovations involve the development or application of significantly new technologies or ideas into markets that are either nonexistent or require dramatic behavior changes to existing markets.” (McDermott and O’Connor, 2002)

I’d like to use “Radical innovation — Incremental Innovation” in a broader sense. Let’s use the “Idea/Concept” diagram again. From the perspective of Project-oriented Activity Theory, a “Radical Innovation” can be definitely defined as a project with a brand new concept while “Incremental Innovation” can be understood as a project with a good idea that is not ready for proposing as a brand new concept.

Since Blunden’s approach focuses on “the formation of a project with a concept of the problem is an original and creative social act,” thus, if we only apply it to the “Idea” process without considering other processes, then we are just using a sledgehammer to crack a nut.

Finally, I’d like to suggest some concrete directions for further studies and discussions:

- Micro Movements as Cultural Innovations

- Brand Commons for Social Change

- Concept Competition and Career Development

- Knowledge Development and Domain Formation

- Digital Technology and Business Development

You can find more details in Chapter 13. Also, you don’t have to adopt the whole theoretical approach for your project. You can use one or two concepts.

For example, I recently developed a new framework called Concept-fit for discussing Platform Innovation. I used the notion of Concept from Blunden’s approach as the foundation and developed two types of concepts: Technological Concepts and Sociocultural Concepts. Again, I also adopted ideas from Ecological Psychology. By curating these ideas together, I developed a new framework for discussing “Technology - Culture Fit” which is the core of Platform Innovation.