A Typology for Anticipatory Activity System

A Significant Insight I learned from the Anticipatory Activity System (AAS) project

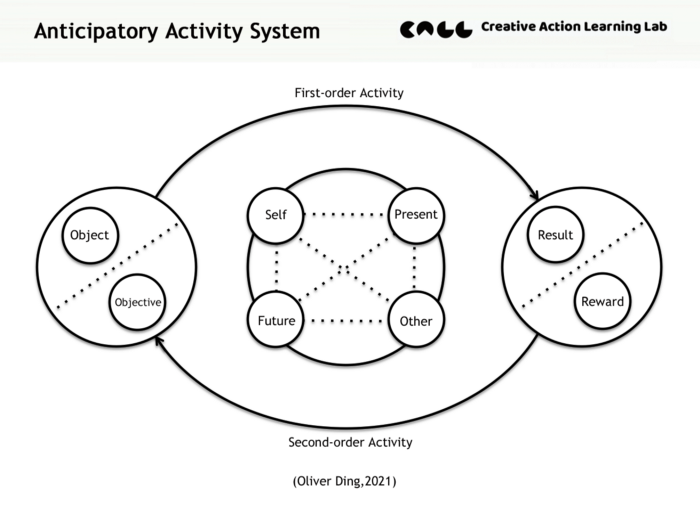

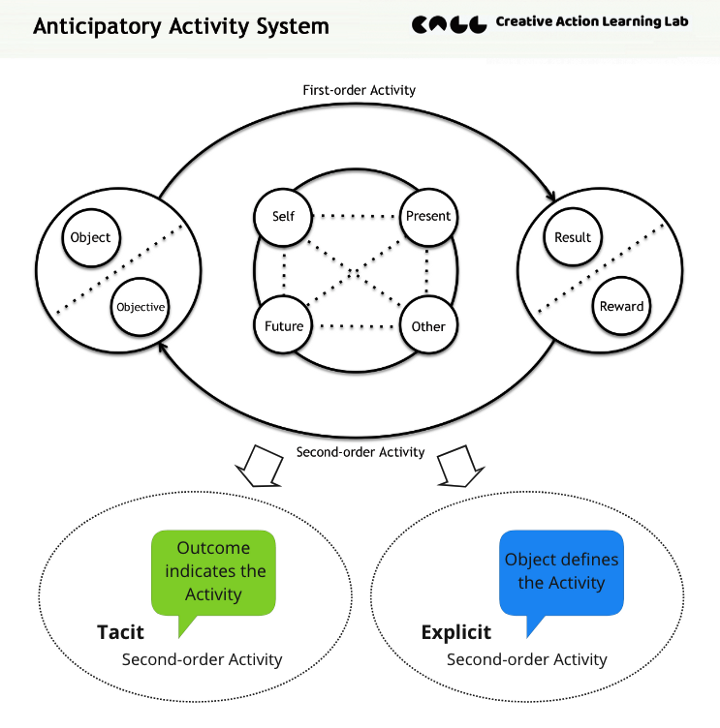

The above diagram is the basic model of the Anticipatory Activity System framework which is inspired by Anticipatory Systems theory, Activity Theory, and other theoretical resources.

The AAS framework was born on Sept 15, 2022. Initially, it was developed for thinking about the complex of “Self, Other, Present, and Future”. My first article about the AAS framework is about applying it to Strategy, you can find more details in Strategy as Anticipatory Activity System.

In the past year, I worked on testing the AAS framework by conducting empirical research. You can find more details about the journey in Slow Cognition: The Development of AAS (August 21, 2021 - August 26, 2022).

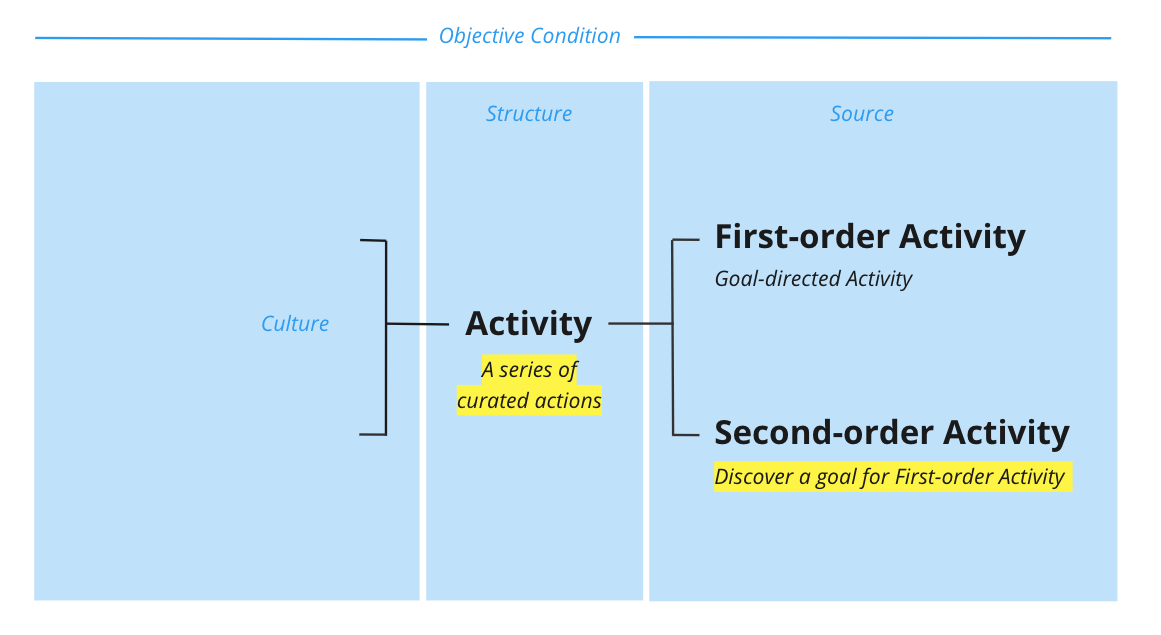

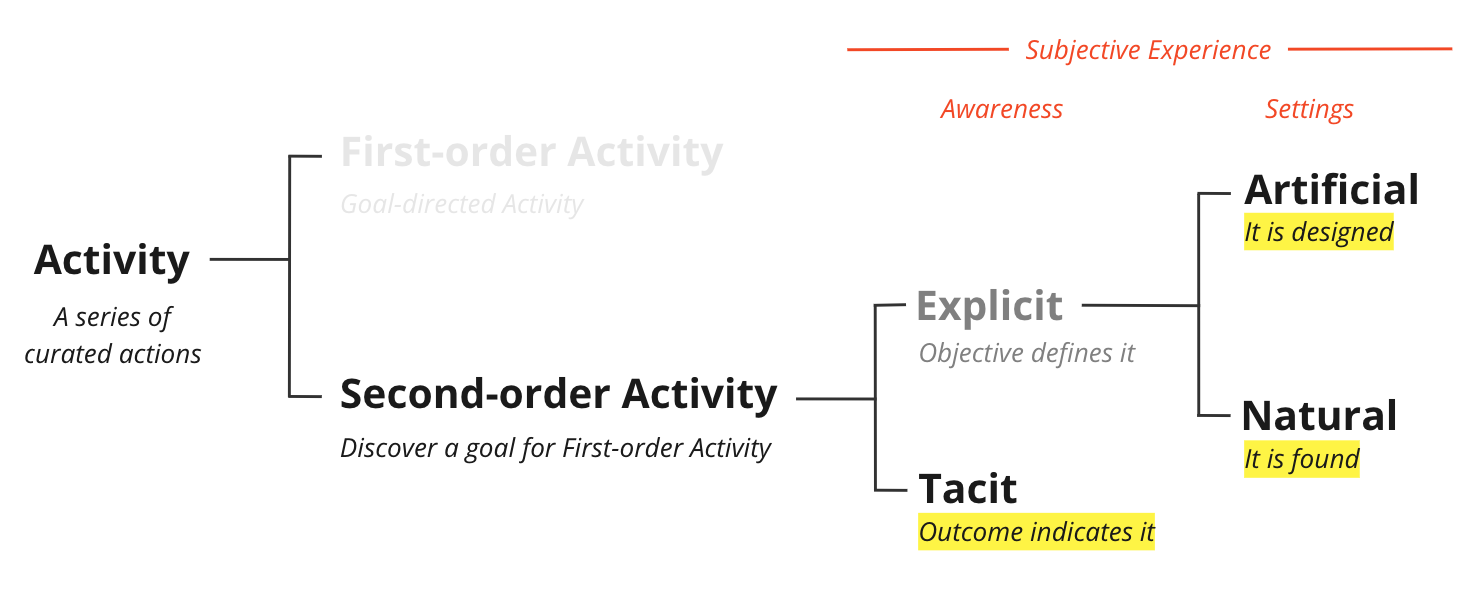

A primary pair of concepts of AAS are First-order Activity and Second-order Activity. While First-order Activity refers to goal-directed Activity, Second-order Activity refers to discovering a goal for First-order Activity.

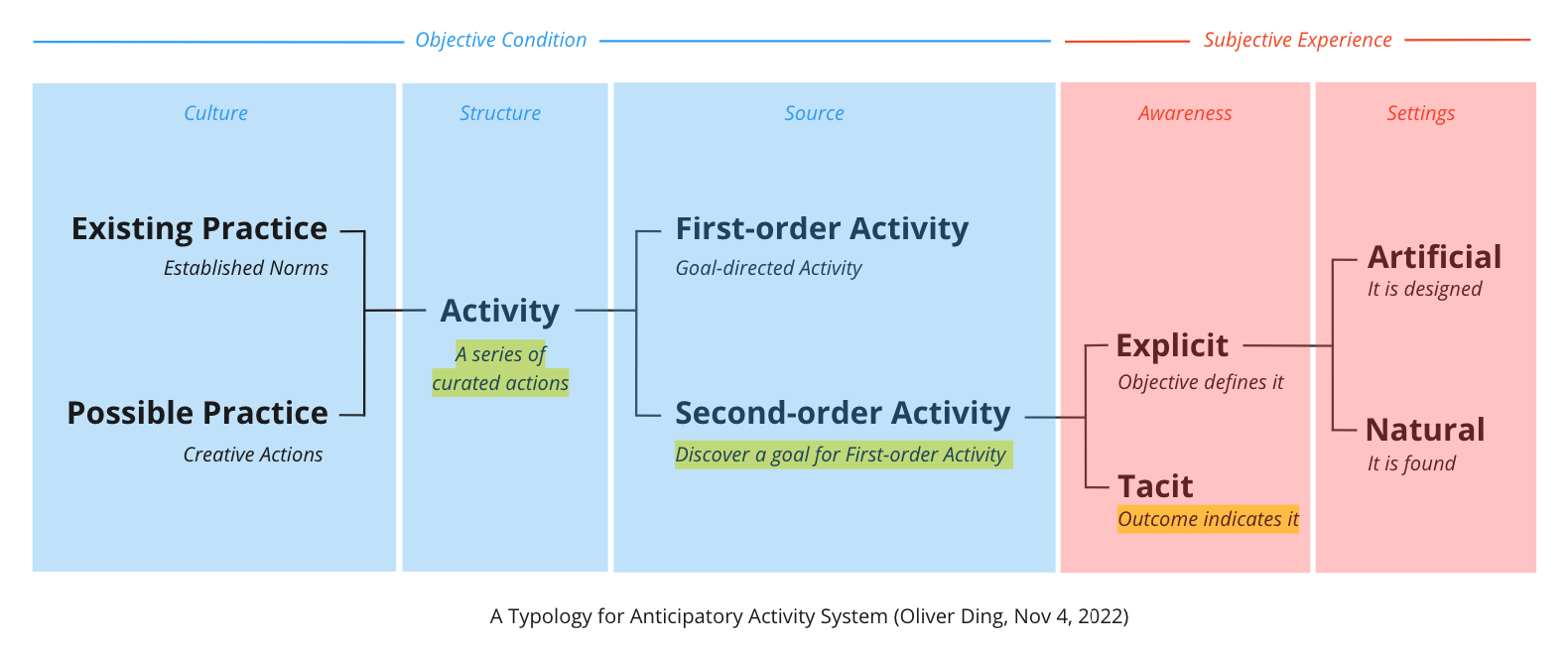

Eventually, I develop a new typology of Activity. See the diagram below.

The above diagram is a significant insight I learned from the AAS project. This article aims to provide more details about the typology of activity.

Typologies of Activity

Typology is a typical knowledge container in many fields. Typology is a great tool for learning and using theories. We can consider typology as a type of intermediate knowledge for connecting theoretical research and domain practice. As an information architect, I create typologies for curating data and information and designing websites and app structures. I also collect typologies for learning new knowledge.

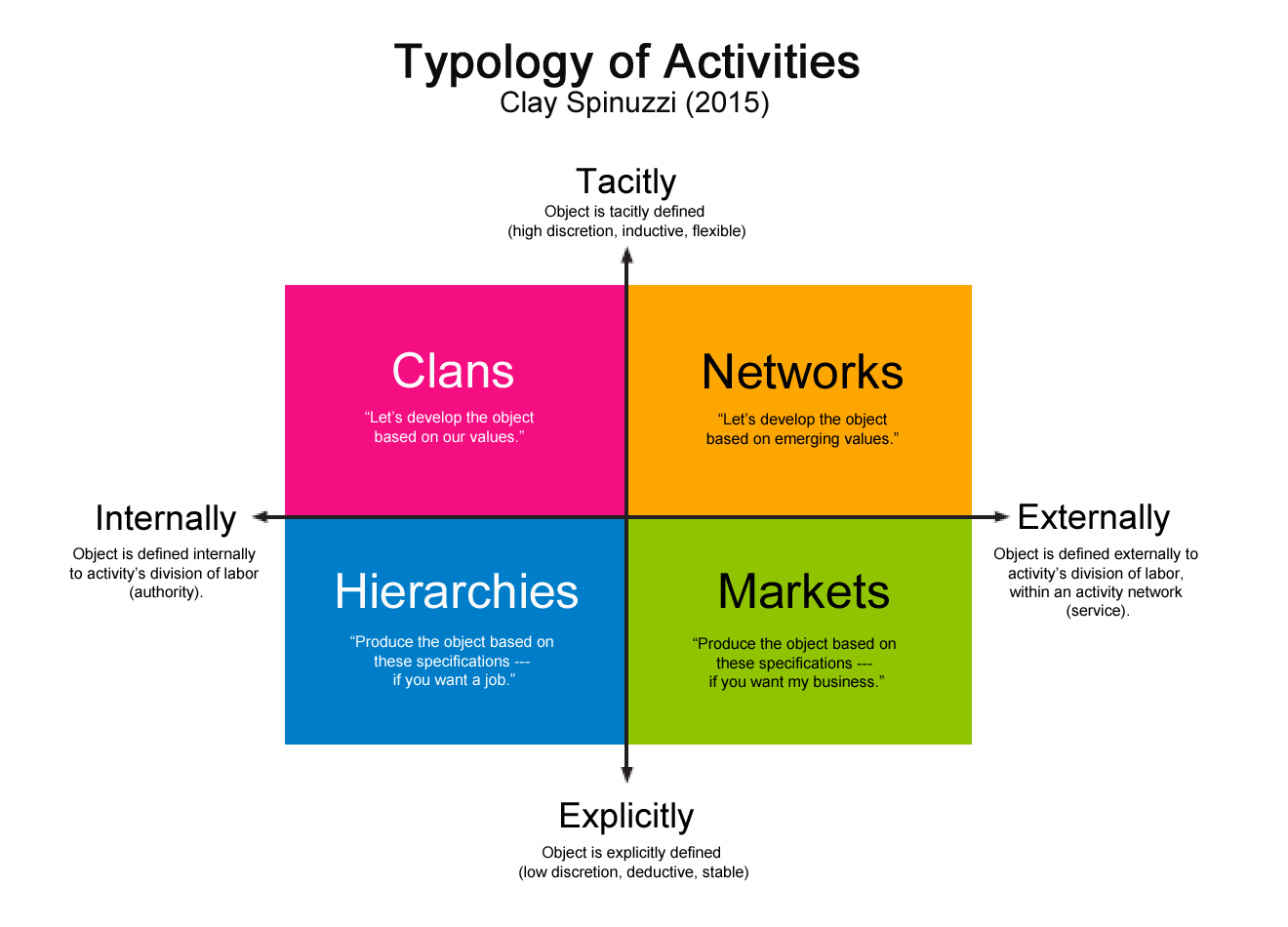

In 2014, I started learning Activity Theory. After reading some books and papers about Activity Theory, I moved to search for some typologies of activities. In 2015, I found Clay Spinuzzi’s paper Toward a Typology of Activities: Understanding Internal Contradictions in Multiperspectival Activities. He pointed out, “AT (Activity Theory) currently lacks a suitable typology for characterizing ideal types of activities in terms of multiperspectivity, so it has had trouble systematically characterizing the resulting sets of internal contradictions.”

Spinuzzi (2015) summarized several typologies made by other activity theorists before presenting his own idea. For example, “Y. Engeström (1987) characterized activities in terms of craft activity, rationalized activity, humanized activity, and collectively and expansively mastered activity…In his later work, Y. Engeström (2008b, pp. 190–191) drew on Victor and Boynton (1998) to describe historically different types of production (craft, mass production, lean production, mass customization, and coconfiguration), each with its own objects and contradictions.” Spinuzzi commented on Engeström’s typology and pointed out its limitation, “…this typology depicts a historical progression of separate ideal types of activity with separate axes, not a matrix with the same axes — making comparison difficult. ”

Other activity theorists created typologies of activity with a 2x2 matrix format. For example, “…Engeström, Brown, Christopher, and Gregory (1997) used a matrix with the axes of flexibility and collectivity to characterize a zone of proximal development whose quadrants represented professional craftwork, market-driven case management, bureaucratically regulated work, and informal, networked processing…Jarzabkowski (2003) proffered a typology of activities based on the axes of actors, collective structures, and strategic activity…” Spinuzzi argued that “these matrix-based typologies have tended to not be broadly applied, serving rather as a way to characterize specific cases. More important, they have tended to not illuminate internal contradictions based on competing perspectives within the activity.”

Spinuzzi came to the conclusion that there is a need to make an ideal typology of activities for general purpose to “explore internal contradictions resulting from hybrid activities”.

In 2015, Spinuzzi developed a typology of Activity with the following two dimensions:

- How is the object defined? Is it defined explicitly and deductively or tacitly and inductively?

- Where is the object defined? Is it defined within the activity’s division of labor or outside it?

The outcome is a matrix with four quadrants (see the diagram below) which represent four ideal activity types.

Spinuzzi named these four ideal types of activities as Hierarchies, Markets, Clans, and Networks. We have to notice these words are just names of ideal types. Spinuzzi said, “I use the term markets in the sense of most organizational typologies (e.g., Adler & Heckscher, 2007; Boisot & Child, 1999; Boisot et al., 2001; Cameron & Quinn, 2011; Ouchi, 1980; Ronfeldt, 2007), not strictly in the sense of commerce. Clan may be too precise; I prefer Adler and Heckscher’s (2007) ‘community.’ But the term community already denotes a different concept in activity theory.”

Spinuzzi's typology can be seen as a typology of First-order Activity. You can find more details in A Typology of Activities.

My typology is a typology about both First-order Activity and Second-order Activity.

Activity as A Series of Curated Actions

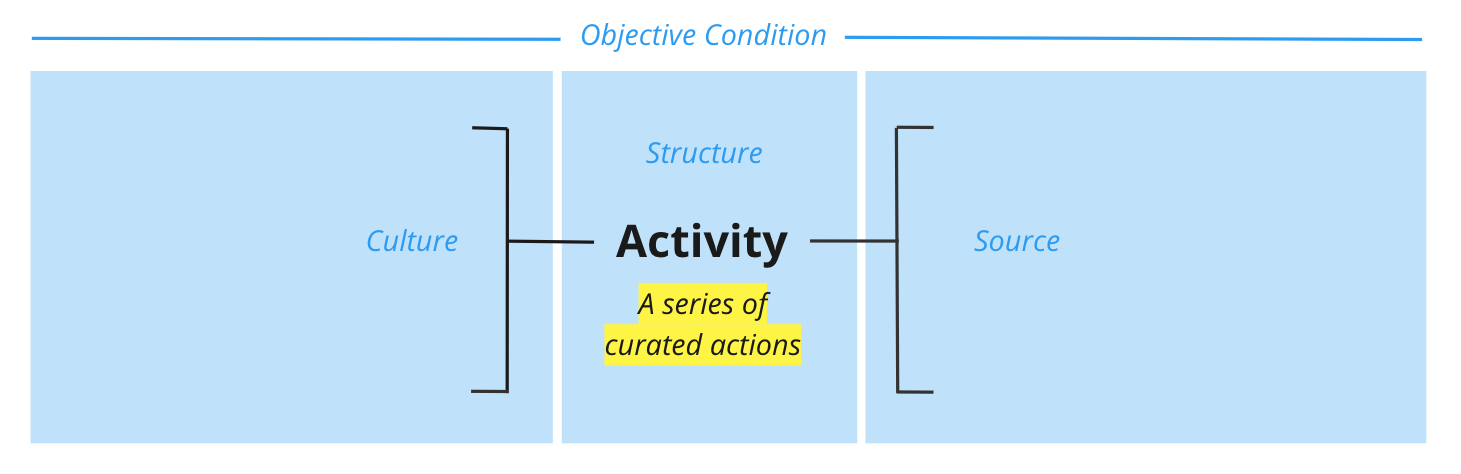

My typology starts with the following working definition of Activity.

Activity as a series of curated actions

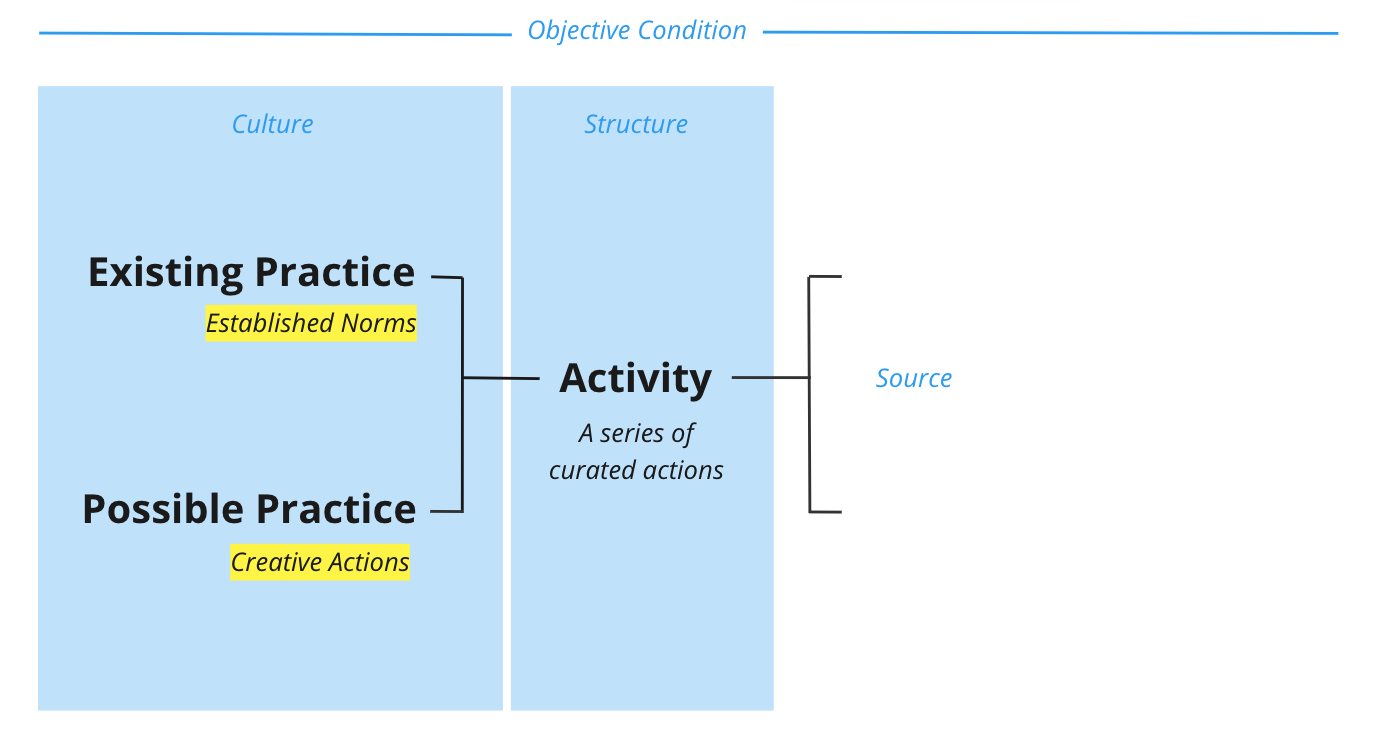

The first part of my typology is about Objective Conditions which contain the following three dimensions:

- Structure

- Culture

- Source

The Structure dimension refers to the relationship between Activity and Actions. According to Andy Blunden, "An activity or project is an aggregate of actions... the activity is generally a precondition for any of the component actions."

According to Andy Blunden, "In Activity Theory, there is nothing in an activity other than human actions, and this is a thesis with which contemporary interactionist theories would be in agreement, eschewing resource to biological determinism, religious or structural fatalism or any other force outside of human action as determinants of human life." However, Blunden emphasizes:

But because there is nothing other than human actions to be found in an activity this does not mean that an activity is simply the additive sum of actions. In fact, the activity is generally a precondition for any of the component actions which instantiate it: when we act we do not generally create an activity, we join it. So Activity Theory recognizes that there are aggregates of actions which have a unity of their own for which, as the saying goes, the whole is greater than the sume of the parts. (Andy Blunden, 2014, p.24)

There are several solutions for conducting the relationship between part and whole in Activity Theory.

From my empirical research, I discovered several types of Activity. In order to develop a new typology, I use "Activity as a series of curated actions" as a working definition of Activity.

This is my understanding of the Structure dimension of Activity. It's the starting point of a new typology.

The Source of Activity

The traditional Activity Theory considers Activity as object-oriented activity. For the AAS framework, it refers to First-order Activity. There is a goal or an objective, then the goal directs a new activity.

However, where does an objective or a goal come from?

What will happen when a person doesn't have a clear objective or a goal?

This situation will lead to Second-order Activity which aims to discover an objective or a goal for a new activity, a First-order Activity.

What's the value of the distinction between First-order Activity and Second-order Activity?

It offers a solution to understand the Source dimension of Activity. Where does a First-order Activity come from? It comes from an Objective or a goal. Where does the objective come from? It comes from a Second-order Activity.

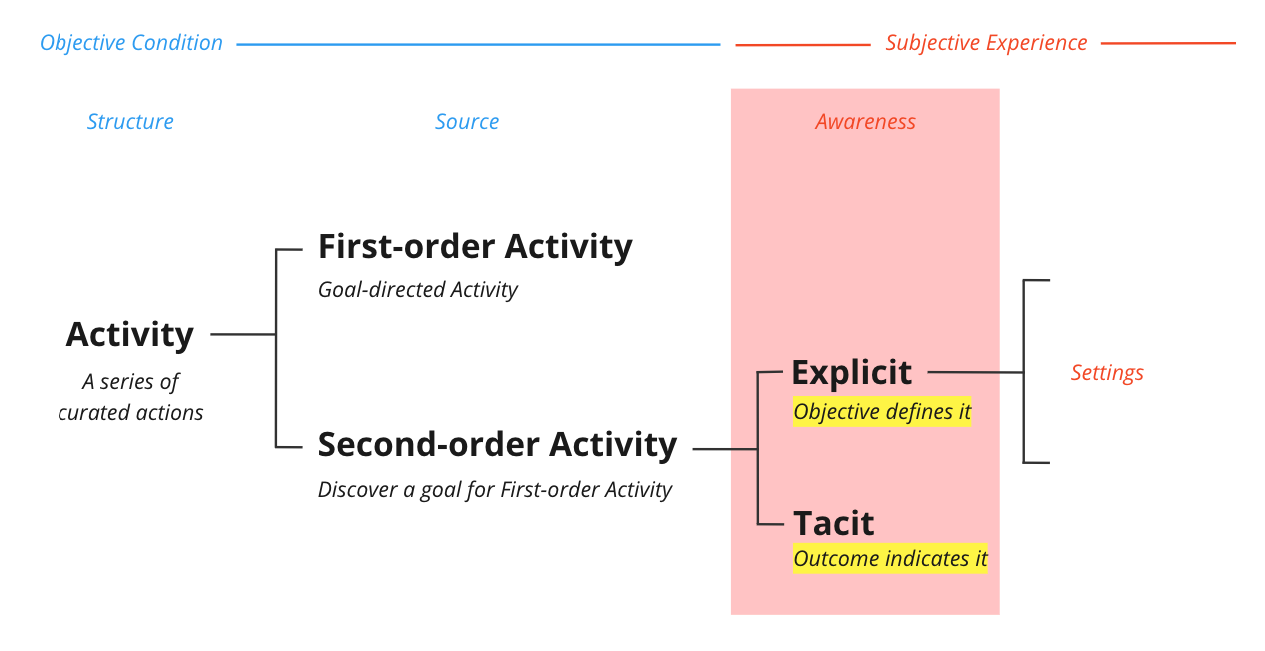

The Subjective Experience of Activity

The second half of the new typology is about Subjective Experience which considers the following two dimensions:

- Awareness

- Settings

For the Awareness dimension, I discovered two types of Second-order Activity.

The Explicit Second-order Activity is defined by the Objective while the Tacit Second-order Activity can be indicated by the Outcome.

You can find more details in Life Discovery: The “Tacit” Type of Second-order Activity.

Three Types of Second-order Activity

From my empirical research, I also discovered three types of Second-order Activity:

- Artificial (Explicit Second-order Activity)

- Natural (Explicit Second-order Activity)

- Tacit Second-order Activity

These three types of Second-order Activity are highlighted from the perspective of Subjective Experience.

1. Artificial (Explicit Second-order Activity)

For example, a person joins an adult development program to run a Life Discovery Activity. The program is an artificial setting.

2. Natual (Explicit Second-order Activity)

For example, a person runs a podcast and considers it as a Life Discovery Activity.

3. Tacit Second-order Activity

A person doesn't know there is a Life Discovery Activity in his life. However, he perceives a significant insight about something. He reflects on the journey which leads to the significant insight.

This journey is a Tacit Second-order Activity.

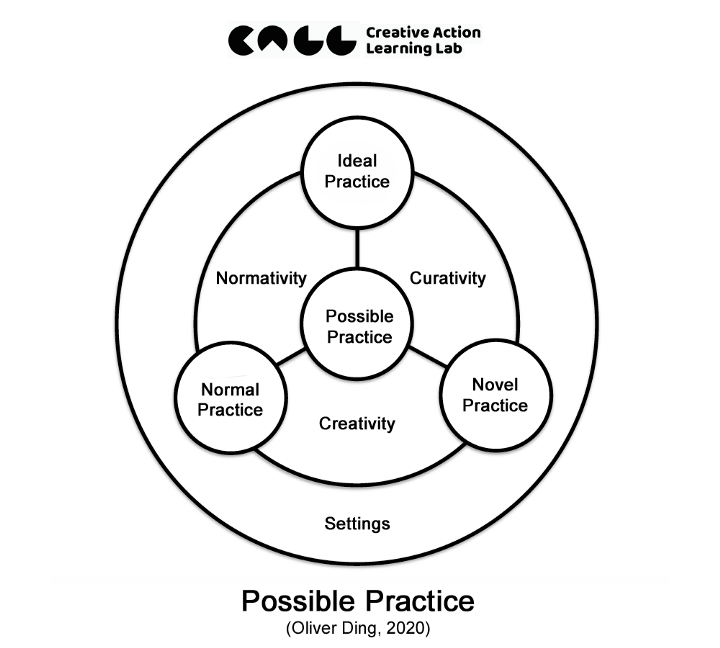

Possible Practice

The perspective of Objective Condition also considers the Culture dimension which refers to the Cultural Historical Development of Activity as social practices. See the diagram below.

The above diagram only lists two types of social practices: Existing Practice and Possible Practice.

You can also find more details in the diagram below and The NICE Way and Possible Practice.

I consider actions at the individual level and practice at the collective level. The four types of social practices correspond to four types of actions.

- Possible Practice — Possible Actions

- Normal Practice— Normal Actions

- Novel Practice — Creative actions

- Ideal Practice — Exemplary Actions

Why do I place Possible Practice at the center of the new framework? I consider the possible practice as the origin of all types of practice. If we trace back to the historical development of any social practice. We can always find that their sources are possible actions. In order to build the concept of Possible Practice, I use Possible Actions to replace Imagined Actions. I consider affordance and imagination are two sources of possible actions.

If we put Normal Practice, Novel Practice, and Ideal Practice into one category: Existing Practice, then we can get the diagram below.

Since 2001, a group of philosophers, sociologists, and scientists have rediscovered the practice perspective and used it as a lens to explore and examine the role of practices in human activity. Researchers called it The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. As Schatzki pointed out, “there is no unified practice approach”(2001, p.2). Davide Nicolini adopted a way of toolkit to introduce the following six different ways of theorizing practice in his 2013 book Practice Theory, Work, & Organization:

- Praxeology and the Work of Giddens and Bourdieu

- Communities of Practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991)

- Activity Theory / Cultural-historical activity theory (the Marxian/Vygotskian/Leont’evian tradition)

- Ethnomethodology (Harold Garfinkel, 1954)

- The Site of Social (contemporary developments of the Heideggerian/Wittgensteinian traditions, by Theodore R. Schatzki)

- Conversation Analysis / Critical Discourse Analysis (the Foucauldian tradition)

Nicolini also pointed out, “Practice theories are fundamentally ontological projects in the sense that they attempt to provide a new vocabulary to describe the world and to populate the world with specific ‘units of analysis’; that is, practice. How these units are defined, however, is internal to each of the theories, and choosing one of them would thus amount to reducing the richness provided by the different approaches.” (2012, p.9)

I suggest “Possible Practice” as a new term that expands the scope of contemporary practice theories from “actual actions and existing practice” to “possible actions and possible practice”.

The Complexity of Life Strategy Activity

The AAS framework was born from the Life Strategy Project. If we apply this new typology to understand Life Strategy Activity, we can see its complexity.

For the Life Strategy Activity, I defined the following activities:

- Second-order Activity: Life Discovery Projects

- First-order Activity: Developmental Projects

Thus, we see many types of activities in Life Strategy Activity. The complexity of Life Strategy Activity doesn't only refer to the structure of Life Activities but also moves between different types of Life Activities.

You can find more details from the related articles below

- Life Discovery: Running A Developmental Project

- Life Strategy: Kinds of Project Engagement

- Life Discovery: The Predictive Model and Anticipatory Activity System

What a challenge!

It's so complicated for ordinary people.